Paul Kalanithi taught me that death is surprising, even to someone well-acquainted with it. Alongside Kelly Corrigan, I cried about the fact that parents aren’t eternal and regrets come to bite you at the most inopportune time. Cheryl Strayed made me yearn for the open road while also realizing you can never get a true do-over, no matter how well-deserved. The power these memoirists held over me relied on their writing’s timelessness and applicability. In fact, memoirs are the one genre of literature that combine the raw, personal appeal of anecdotal writing with an attractive element of self-help. Through authors’ own lives, I acquainted myself with various spheres of life– college, marriage, parenting– while still living a relatively cloistered high school existence. These narratives were a wake-up call to the things I always knew, the things I might learn someday, and the aspects of life I needed to change for myself. But if memoirs are practically instant conduits to vicarious learning, why are they rarely introduced in high school curriculum or read by young adults recreationally?

Image via LibreShot

When considering memoirs’ ability to increase emotional acuity in readers by noticing action-consequence patterns in authors’ lives, this genre is a highly-appropriate remedy for today’s teen emotional intelligence crisis. An such a crisis does exist: in recent years, college students’ empathy levels dropped close to 40% compared with their pre-2000s counterparts. Though empathy is just one component of overall emotional intelligence, it is an important indicator. Research has also found that in today’s educational environment, cognition and intelligence dominate while social-emotional skills are largely left to students and parents to develop and reinforce. Unfortunately, this doesn’t fare well when examining a student’s life longitudinally: in workplace scenarios, a low EQ, or emotional quotient, is a higher disadvantage than having a low IQ.

Self-awareness, the ability to understand others, knowing how to manage your emotions, and quickly recognizing emotional reactions all constitute essential skills that need to be taught to the next generation of successful employees or leaders. Educational centers and research labs are taking steps to introduce specific measures for how to teach these vague and non-quantifiable assets to students, but many efforts revolve around mere conversation or group activities and are not streamlined to be universal.

Letting young adults read memoirs is an alternative form of emotional development which might revolutionize the way students are taught real-life skills in the classroom. By engaging in another person’s narrative and taking part in their journeys “through the page,” youth can bypass the awkwardness or rigidity of mediated discussion and gain direct insight about the intricacies of what makes us all human, in turn becoming more emotionally competent.

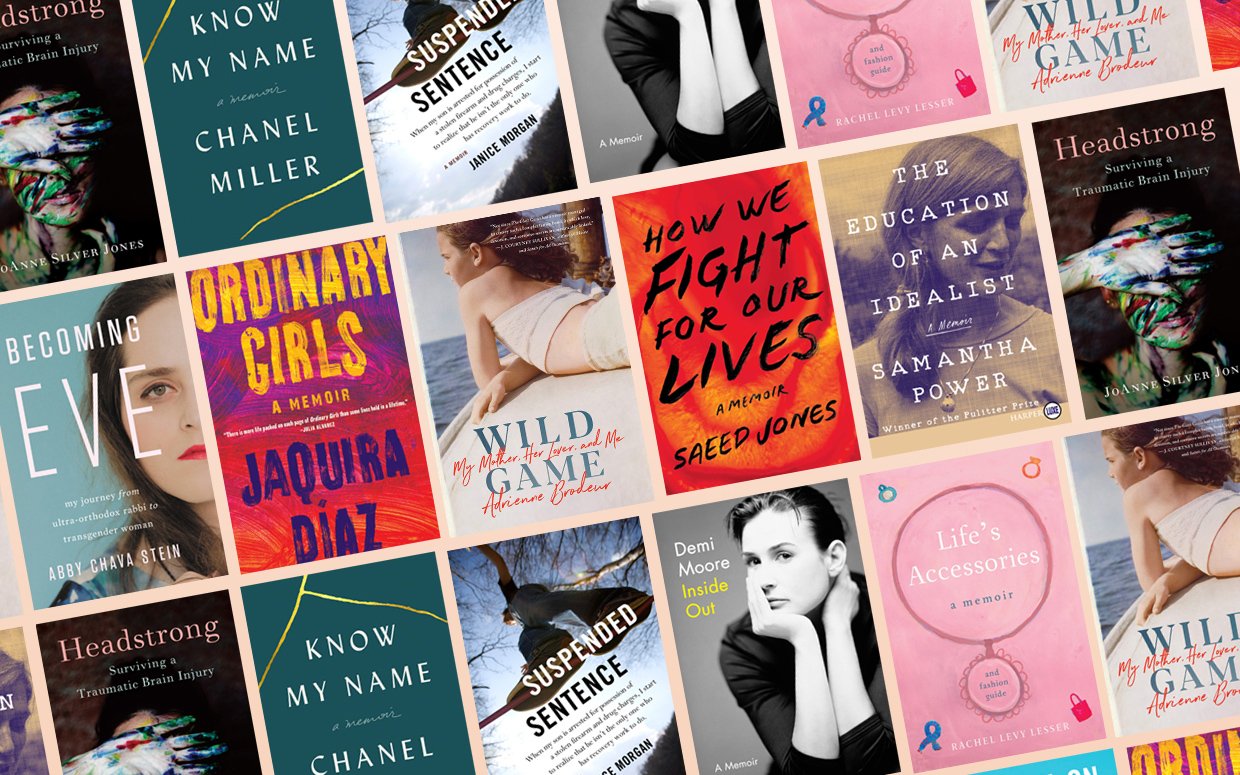

Image via Parade

To be sure, English curriculum in American secondary education does not shun reading as a method of self-discovery. It places a heavy emphasis on works of fiction, including titles written from a first-person point of view (Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Warren’s All the King’s Men, among others) that seem comparable to real-life, non-fictitious storytelling. Yet, much of the fiction literature taught in schools holds principles that seem like holdover from another era altogether: one today’s teens cannot and, quite frankly, do not wish to understand.

As Avery Rodgers wrote so eloquently in 2017 for the Stanford Daily, describing being disillusioned by the great novels of our time, “fiction had a heroic depth that…did not align with the slightly-amusing banality of my daily existence. My misfortunes did not feature battle scenes… but things like losing friends, negotiating petty family grievances, juggling self-criticism and self-compassion and thinking about what the hell I was going to do with my life.” Teens crave (and deserve) a body of literature that holds more meaning to their immediate circumstances, rather than trying, fruitlessly, to relate to the struggles of Greek heroes or medieval knights or 20th century Englishwomen.

Though memoirs are not necessarily an accurate representation of teen life and teen struggles (most are written by fully-formed adults with abundant stories to share), the genre allows teens a “sneak peak” into future possibilities versus being a relic from a different time altogether or a fantastical and overexaggerated version of the universe.

Sure, kids might never find out the outcome of Atticus Finch’s famed court case or how many levels of hell Dante thought there were.

But reading more memoirs and less classics in classroom settings or promoting students’ independent enjoyment of the genre will create a young audience that is more receptive to good writing, compelling stories, and the deeply human, deeply flawed thing we call life.

And that counts for something.

Featured image via Negative Space