“In this world of ours, the sparrow must live like a hawk if he is to fly at all.”

— Hayao Miyazaki

The final batch of Studio Ghibli films have become available on Netflix this April, joining a long list of others that came before. The highly-respected Japanese animation film studio is responsible for their notable works such as the all-around favorite My Neighbor Totoro, the Oscar-winning Spirited Away and many more. If you’ve watched even one of them, you’ve most likely become a willing victim of its trademark magic.

Hayao Miyazaki. Source: Wikimedia

Fortunately for us, we can catch a glimpse of the making of its magic. According to Indiewire, NHK has recently made available online (for free!) 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, a four-part documentary on the esteemed filmmaker’s creative journey. To add another layer of good news, Miyazaki is coming out of his previously announced retirement in 2013 to direct a new film titled How Do You Live?, slated for a 2021 or 2022 completion. So naturally, now is a good time as any to revisit and reflect the prolific Miyazaki’s works.

Try this: Take all of Studio Ghibli’s films, spread them on a table, pick a favorite. Almost everyone will have a different answer (or answers, because it’s hard to choose just one). However, if you look deeper into these films, beneath the fairy tales lie themes ranging from finding one’s true meaning in life to a subtle discourse on war.

For me, what I’ve discovered is that in the heart of many of them, especially ones helmed by Miyazaki himself, is the true love and longing for flight and the skies.

Sheeta, Pazu, and the pirates from Castle in the Sky. Source: Netflix

Miyazaki’s first official feature with Studio Ghibli was Castle in the Sky (though considered a Ghibli film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was released before the studio’s official founding). Released in 1986, the film chronicles around a cast of characters consisting of a boy and a girl, government agents, and pirates — all on the hunt for a magical floating castle. As the castle is somewhere in the sky, the film mainly takes place high above the ground as well.

If you take a closer look at each of the three parties’ (the children, the pirates, the agents) quests, there is a difference of purpose and use of aviation in their pursuit. The children, Sheeta and Pazu, are seen to use small kite-like contraptions, the pirates equipped with a large carrier and smaller wasp-looking ships, and the agents with their giant military airship, conveniently named Goliath. This showcases how one thing can have different meanings to different people. Life is like that. Don’t forget to pay attention to the perspective.

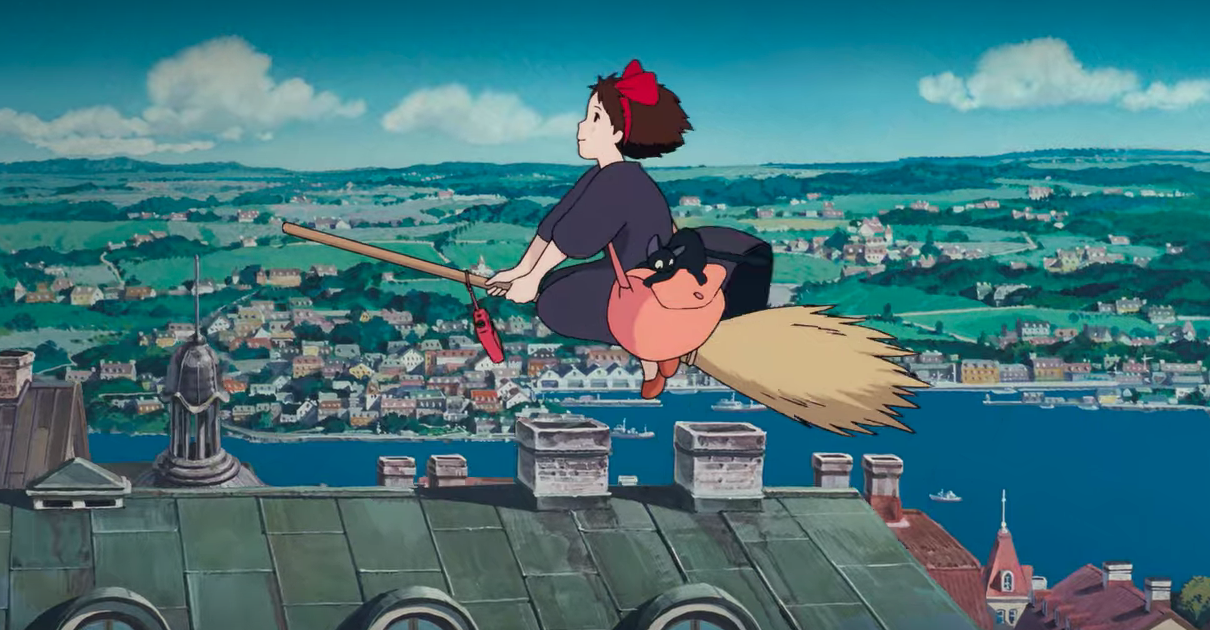

Teenage witch Kiki and her cat, Jiji, take flight in Kiki’s Delivery Service. Source: Netflix

There were no lessons lost in one of his next works, Kiki’s Delivery Service. The titular Kiki is a Sabrina-esque teen witch-in-training who leaves home for a year, but not without the typical witch paraphernalia in tow: a broomstick and a black cat. In going solo, flight serves as Kiki’s superpower in her brand new delivery business. This film also touches on what happens when we lost our superpower — our purpose — and what we need to do to bring it back.

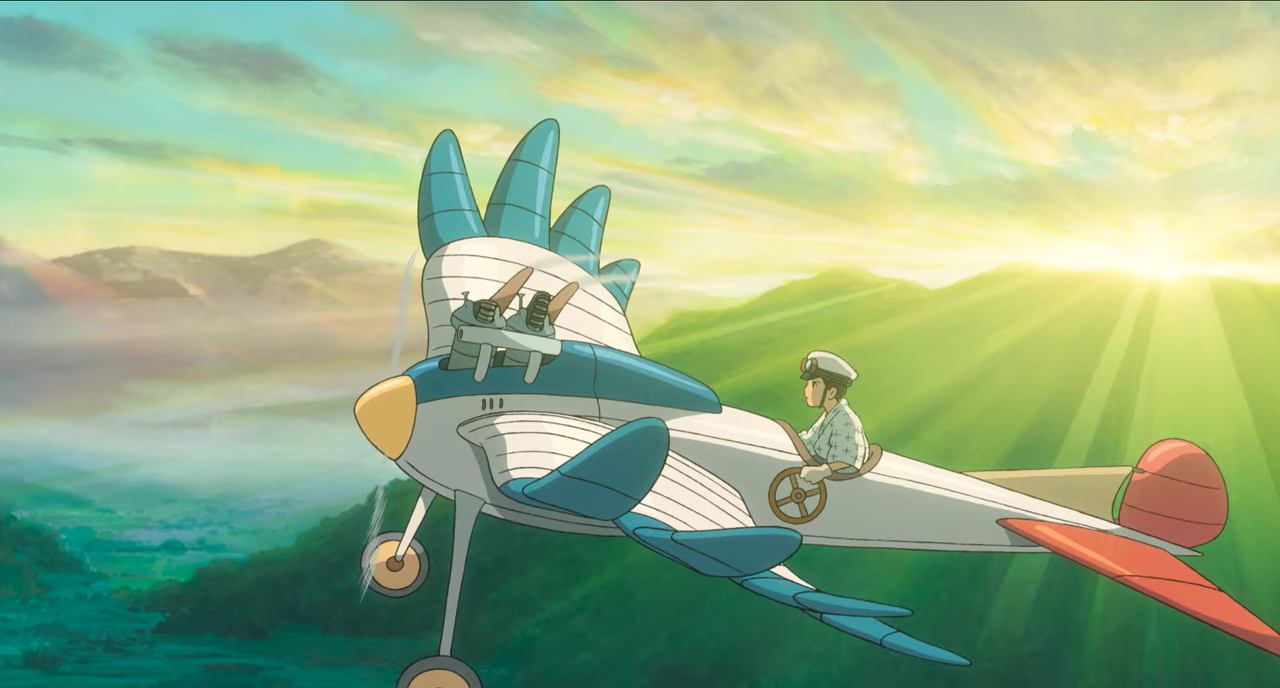

Miyazaki’s last — but most certainly not least — film before his semi-retirement is 2013’s The Wind Rises, an imagining of the life of engineer Jiro Horikoshi, known for designing the Mitsubishi A6M Fighter in the Second World War. In this particular work, Miyazaki did not shy away from crafting a character so deeply devoted to his passion. And in the case of Jiro, it’s planes.

What makes The Wind Rises different from its sky-admiring counterparts is it’s a departure from the child-like fantasies of witchcraft and castles. In this film, flight takes a literal, mechanical shape in the literal, mechanical realities of war. But Miyazaki did not leave us with nothing.

Instead, he gifted Jiro with vivid imagination. Dream scenario after dream scenario, the protagonist lived and grew through them. Although magic is not present in this world (which is our world), Jiro’s romanticism of airplanes makes a worthy replacement. And even when his expectations were disappointed by reality, he kept living.

Howl and Sophie take a leap in Howl’s Moving Castle. Source: Netflix

Among his other films, many of Miyazaki’s characters are equipped with the capacity to fly (Haku from Spirited Away), walk on air (Howl from Howl’s Moving Castle) or manuever an aircraft (Porco from Porco Rosso).

Watch these films again, pay close attention to how detailed and carefully drawn the motions of flight and bodies of aircrafts are. An extraordinary amount of precision and care are taken in bringing them to life. In their effort to capture flight as real as possible, they are cautious in not letting creativity go astray. In both airships or broomsticks, the imagination is always satisfied. It is no wonder that Studio Ghibli films are champions in magical realism.

However, Miyazaki’s love of flight never surpasses the devotion he has for his characters. Flight is a companion in his heroes’ journey, but the journey itself is fully theirs. Sheeta and Pazu searching for a home, Kiki finding a new purpose, and Jiro achieving his dreams.

Young Jiro dreams of flying an imaginative airplane, from The Wind Rises. Source: Netflix

One famous quote by Miyazaki is “do everything by hand, even when using the computer.” The computer, like flight and aviation, is a wonderful discovery, but it is merely a person’s tool. The person is still the center of the story, and if they learn to use the tool well, they might just achieve a great many things.

And finally, with that being said, if you think about it, if he lived in the Four Nations, Miyazaki would’ve been an airbender.

Featured image is a screenshot of The Wind Rises from Netflix.